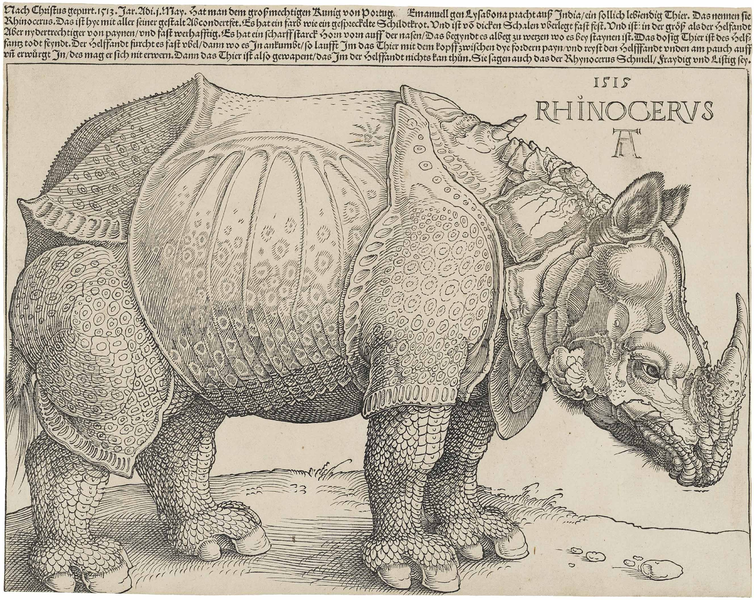

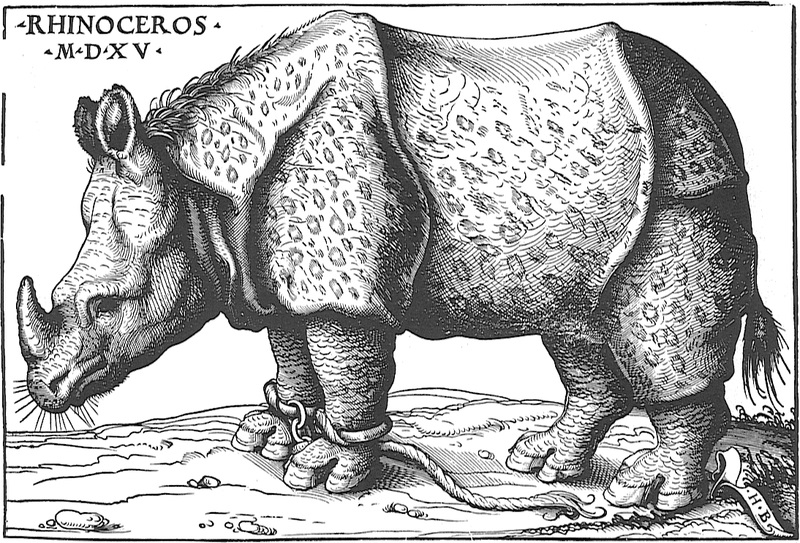

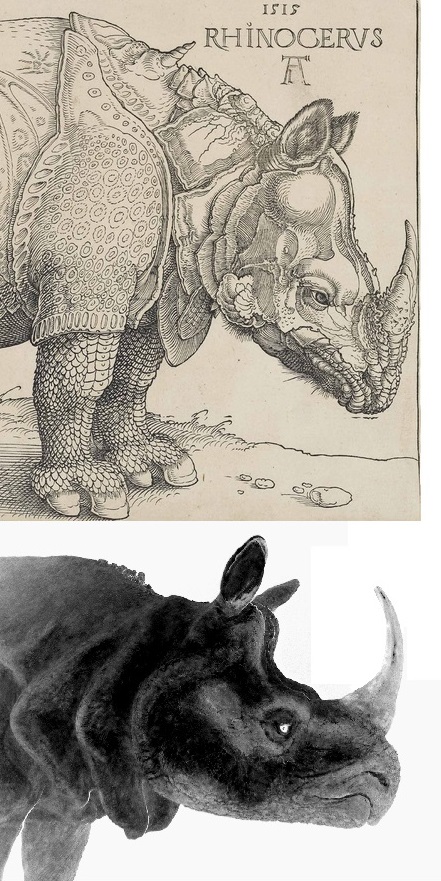

The woodcut of Albrecht Dürer´s „Rhinocerus“ is certainly one of the most iconic animal depictions of the Renaissance. Dating from 1515, a time when books about natural history still usually showed wild mixes of real animals and fully fantastic beings side by side, it is one of the very first depiction of a rhino in European art, and for centuries, one of the most style-defining.

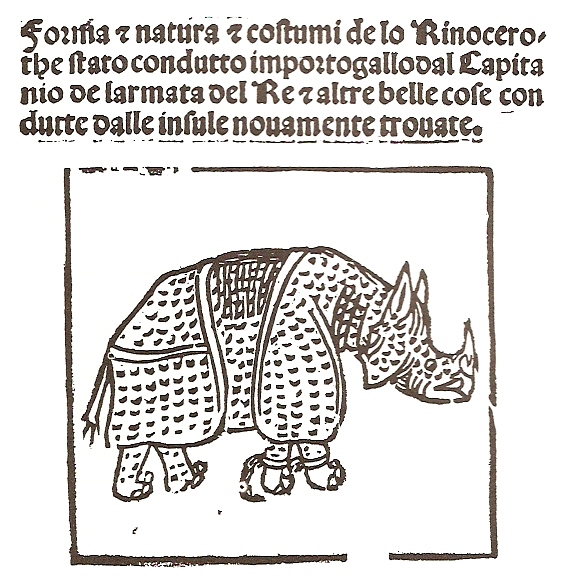

This particular Indian rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) was a specimen which arrived in 1515 after a long odyssey over sea at Portugal, where it lived in the menagery of Ribeira Palace at Lisbon. The earliest known depiction of the Rhinocerus is a pretty crude drawing by Giovanni Giacomo Penni, a florentine physician who wrote a letter with a poem and a sketch of the rhino, which was published in Rome on 13 July 1515, not even eight weeks after the rhino had arrived at Lisbon.

Not much later,in early 1516, it was shipped again as a gift from King Manuel I of Portugal to Pope Leo X. Unfortunately the rhino died when the ship on which it was transported shipwrecked off the Italian coast. The carcass of the rhino was later found on the coast of Villefranche.Its skin was preserved and sent back to Lisbon, where it was mounted as a taxidermy specimen. Not much later, the mounted rhino skin made again its way over sea towards Rome, where it finally arrived after its second voyage.

Albrecht Dürer´s woodcut was based on two letters. One was by the merchant Valentin Fernandez, who sent a letter with a descripton of the rhino to a friend at Nürnberg. He had seen the animal himself shortly after its arrival at Lisbon. A second letter from Lisbon, written by an unknown sender, arrived at around the same at Nürnberg and included also sketch of the rhino.

Pen and ink drawing sent to Albrecht Dürer in 1515, collection of the British Museum. Image from Wikipedia

The similarity to the later woodcut is very big, and only a few details, like the fine serration on the backside, were additionally added by Dürer.

Also in 1515, Hans Burgkmair, a German artist from Augsburg, published a woodcut of the Rhinocerus. He had also correspondence with befriended merchants in Lisbon and Nürnberg, but it is not known if he was aware of the same letters and the sketch used by Dürer. His rhinocerus looks much lesser fancy and extravagant as those of Dürer and appears more realistic, but its proportions and features are arguably not even really closer to the life appearance of an Indian rhino than the woodcut by Dürer.

Dürer´s illustration with the fantastically appearing scales and rivet-like skin pattern, that seems to blend into a crafted yet organic body armour, still amazes with its bizarre beauty. It hast inspired artists for more than half a millenium now, even Salvador Dalí who created a large bronce cast of the rhino. The most unusual feature of the rhino, a tiny twisted horn growing out of its shoulder area, makes it even more appealing to think that Dürer and the unknown illstrator of the foreging pen and ink drawing added a lot of fictional details on the animal for the sake of artistic freedom.

However, those details were probably not even that fictional at all. As weird as the armour-like pattern of the skin looks, it is in fact not that different from the real skin condition of Indian rhinos. Even the gorget-like „neck armour“ is actually not much different from the large neck wrinkles.

The arrangment of the various skin wrinkles is in the main quite close to the real animal. The rivet-like skin bosses are also, even if somewhat exaggerated, both in size and arrangment mainly consistent. It has been suggested that the unusual skin was a result of the long journey over sea in a small enclosure, which could have resulted into a dermatitis or excessive skin growth, but it is quite hard to say if this is really a convincing explanation, especially since the differences between the depictions and the living animal are not that big at al.

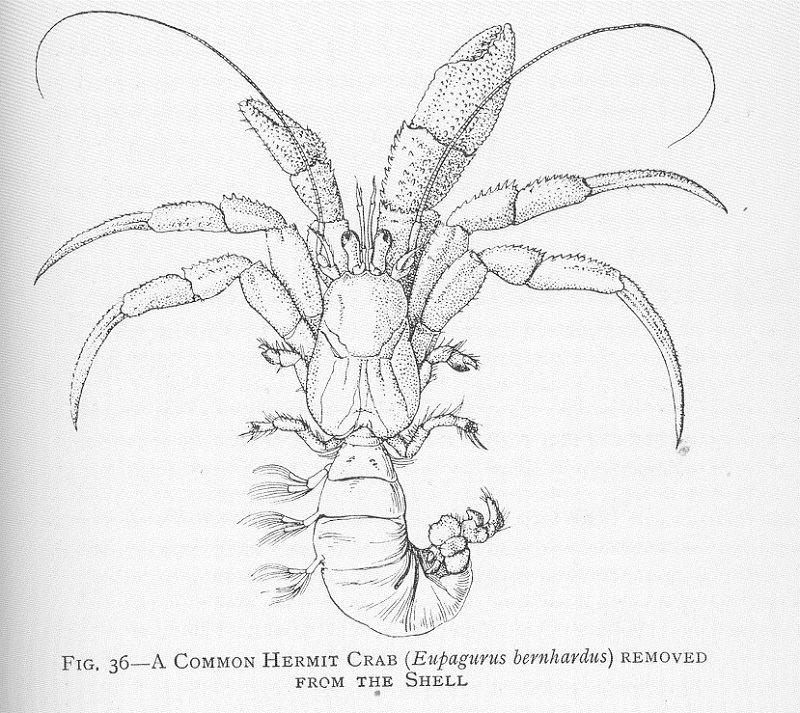

The rivet-like skin-bosses in detail:

The scale-like skin on the legs of Dürer´s Rhinocoeros, which appears strangley misplaced on a mammal, is also only a comparably subtle modification of the real skin pattern. The gnarly surface of the skin really looks much more like those of a tortoise or other reptile with polygonal scale pattern, and even slightly appears to form overlaying „fish“-scale structures on the upper parts of the legs.

So even if the scales on the legs of the Rhinoceros are not fully realistically depicted, they still are not that different from the legs of an actual Indian rhino, even if Dürer and the original illustrator clearly exaggerated and altered the amount and structure of the rhino´s skin to some degree.

For more than a century Dürer´s woodcut was by far the most influential source for depictions of rhinos and was more or less accurately copied for countless times. Even in the 18th century the legacy of the Dürer rhino was found in artistic depiction.

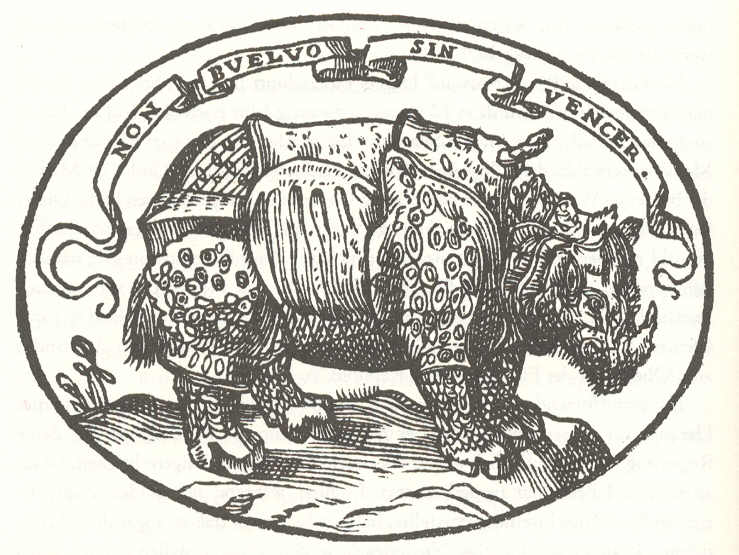

Alessandro de’ Medici even included the rhino, which was obviously highly influenced by Dürer´s woodcut, into his coat of arms.

But what about the most intriguing feature of Dürer´s rhino, the spiraling horn growing out of its shoulder? Ancient artists and scholars who based their description mainly on the few already existing artworks and reports assumed that this horn was really existing. Some even speculated that it was used in intraspecific combats. Some of those depictions show the dorsal horn in an even more twisted and bigger way than the original drawing and woodcut, and there is at least one depiction which shows also a second smaller dorsal horn. The question remains, was it simply a fully imaginary rendition of the unknown illustrator who drew the reference for Dürer´s woodcut at Lisbon?

Well, probably not, at least it was not a fully fictional reinvention. Small horn-like structures are actually known from from white rhinos (Ceratotherium simum), as documented by Bernhard Grzimek and later Karl Shuker (Extraordinairy Animals Revisited, 2007). Based on reports of white rhinos with unusual horns growing on their bodies, Bernhard Grzimek already suggested decades ago that there was possibly a connection with the shoulder horn of Dürer´s Rhinoceros (Thanks to Karl Shuker, who provided me this information). Here is for example a white rhino from Lake Nakuru National Park, which shows three small ceratinous skin growths in its neck area:

White rhino, photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Detail of the shoulder area:

Similar hyperceratoses in the shoulder area also occur in Indian rhinos.

Indian rhino with small hyperceratosis in shoulder area. Modified photo from Wikimedia Commons

Another detail photo:

Indian rhino with hyperceratosis in shoulder area

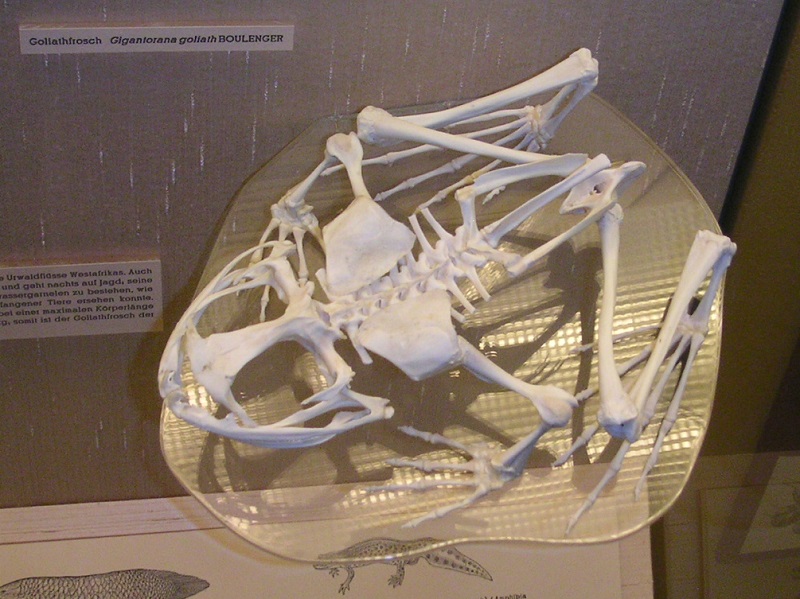

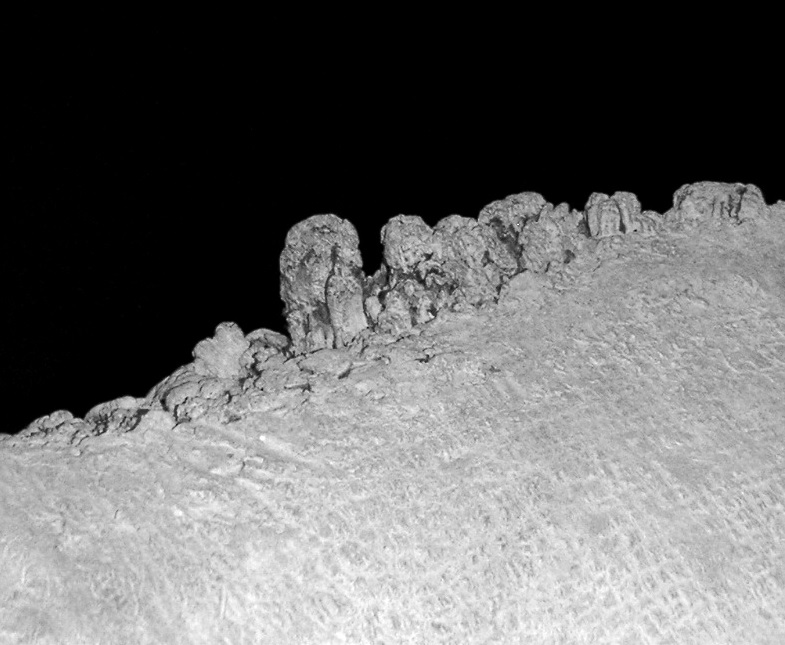

This small areas of excessive skin growths are however still far away from something like a horn, not to mention a twisted narwhale-tusk like horn. But there are even much more extreme cases. When I was many years ago at the zoological collection at Hamburg, I noticed a taxidermied Indian rhino in the collection which had a strange outgrowth in its upper neck area. A row of blunt ceratinous knobs and spikes, from which one was even forming a small horn-like structure.

Indian Rhino, Zoological Collection Hamburg. Photo by Sven Sachs, Naturkundemuseum Bielefeld

At that time I sadly took no photo of the whole specimen, but luckily my good friend Sven Sachs had one from a recent visit of the museum and gave me kindly permission to use it for my blog. Here is a photo I took of the head and neck area:

Indian rhino with shouldern horns, Zoological Collection Hamburg. Photo Markus Bühler

A closer look:

This photo shows the small blunt „horn“

A somewhat modified close-up which shows the surface structure. The „horns“ seems comparably massive and there is also apparantly some wear on their surface.

Detail of ceratinous shoulder horn and humps

Another photo of the rhino which I took in a more frontal view:

Indian rhino with shoulder horns, Zoological Collection Hamburg, Photo Markus Bühler

I can not say what causes this hyperceratosis, if it occurs mainly in very old specimens or if it is even a pathological condition, some sort of skin reaction on external irritations, or if similar growth processes like those of the cranial horns are on work in misplaced areas. A histological examination of such a skin or reports of captive specimens could give probably more answers. The presence of nearly perfectly formed neck- or shoulder horns in some white rhinos indicates however that there actually is a connection of some sort with the cranial horns.

Another case of three comparably large neck-horns in a white rhino from Duisburg Zoo can be seen here. It was a nearly 50 years old female named Nongoma which died in 2014.

A comparison of Dürer´s woodcut with a graphically modified photo the taxidermy specimen from Hamburg. I think it is also noteworthy that there are in front of the spiraled horn also some other, smaller outgrowths on the neck, which are in line with the multiple areas of hyperceratosis found in some of the rhinos shown above.

The twisted horn of the Rhinocerus is clearly a product of artistic freedom, but the horn-and boss-like structures, which really are present in some individual rhinos, show that it was not just a fully fictional decorative element. It would have been a quite extreme case of coincidence if somebody just invented a shoulder horn for rhinos without any knowledge that similar outgrowths really occur in exactly that area. Perhaps there were already older reports from Asia or even Africa which mentioned those shoulder horns, but there is a chance that the rhino at Lisabon was really one of the rare specimens which had such a condition.

(Update): I was also just informed by Connor Lachmanec about a white rhino with a neck or shoulder horn in Vancouver Zoo. This rhino named Charlie has a pretty enormous horn growing of of its neck, which is not just an amorphous growth or callus but a nearly perfectly formed horn. It seems there were possibly once even two other horns which are now broken off. See the amazing photos of Charlie here, here and here.

The simple sketch by Giovanni Giacomo Penni shows nothing that would indicate such a thing. The more detailed woodcut by Hans Burgkmair shows also no horn-like structures over the shoulder or neck, but interestingly he added a mane of bristles on the top of the neck, a feature not found in Indian rhinos. Was it a reinvented detail, perhaps because Burgkmair or his correspondents assumed this animal was somehow similar to a wild boar? Or was it possibly an interpretation of really existing gnarly growth on the neck of this rhino?

We will never know for sure of course. But after this detailed look at the most famous rhino in art history, the Rhinocerus of Albrecht Dürer appears no more that fantastic and made-up as usually assumed, and even some of its more bizarre features like the shoulder horn have quite probably a real origin. So more than 500 years after Albrecht Dürer published the famous woodcut, his marvelous beast has finally redeemed itself to some degree from its overly fantastically appearing depiction.