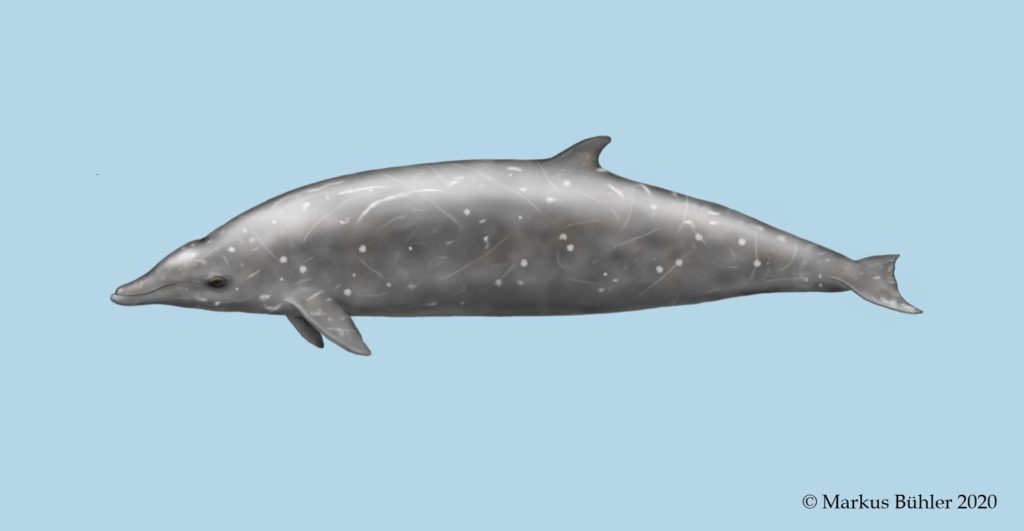

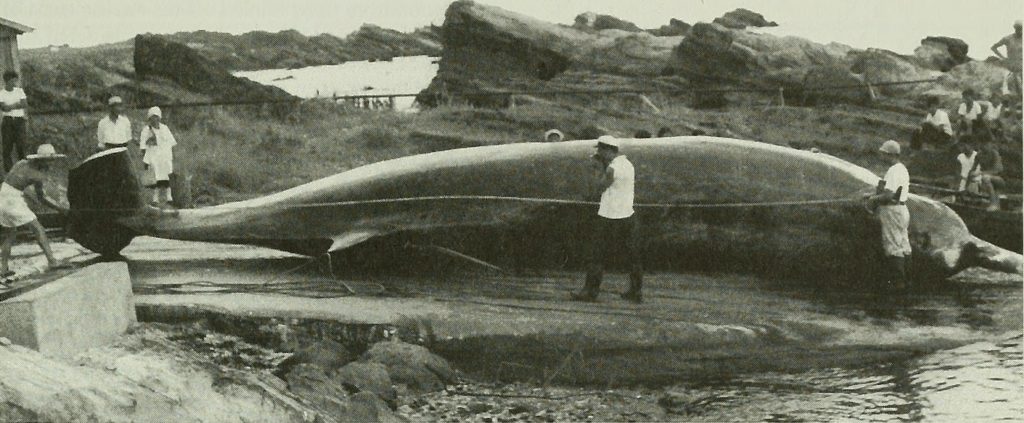

Beaked whales are among the least known cetaceans and even today several species are still only known from a few sightings and stranded specimens. Most people are likely even fully unaware of their very existence, despite the giant size and remarkable appearance of some species. One reason is likely because you will hardly ever see them in a nature documentary because most species are very shy and notoriously hard to find, spend little time on the surface, live in small groups or solitary. This is also the main reason why beaked whales were hardly affected by whaling, with two big exceptions. One is the colossal Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii) which is still hunted for „scientific“ reasons by Japanese whalers. The other exception is the Northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus), which was hunted at industrial scale in the northern Atlantic. Even today they are occasionally caught off the Faroe islands. In contrast to most other beaked whales it spends comparably much time on the surface and is not very shy towards boats, and it occurs in areas which are still comparably close to coasts. It lives in larger groups and the members of the pod usually stay close to injured individuals. This made it easy for whalers to kill many whales after the first one was harpooned, sometimes up to the last member of the pod. As long as the harpooned one was still alive, the others stayed with it.

The other reason why they were hunted was their commercial value. Northern bottlenose whales are among the largest beaked whales and yield a big amount of blubber which was boiled to produce whale oil. And like sperm whales, their melons contain spermaceti, an oil of very high quality and big value. In contrast to the liquid spermaceti of sperm whales the Hyperoodon spermaceti is however of a hard consistency.Hunting bottlenose whales was also much lesser dangerous than the hunt for sperm whales and whalers also needed not as much boats and equipment and had smaller crews. The commercial hunt for bottlenose whales started off Norway, but in later years they were also targeted off Scotland and the northern coast of the American east coast. Since the late 19th century, from 1882 to 1920, about 50.000 Northern bottlenose whales were killed off northwestern Europe alone and commercial hunting at larger scale persisted until the 70ies.

Because the northern bottlenose whale is comparably easy to encounter, dwells in pretty unexotic waters off northern Europe and the U.S. we know much more about it than about other beaked whales. This makes it still somewhat surprising that it is so little known to the general public. Sometimes they make it even into the news, like a specimen which in died in 2006 in the river Thames at London, but normally they are more or less dismissed, even among many people who really have a strong interest in nature.

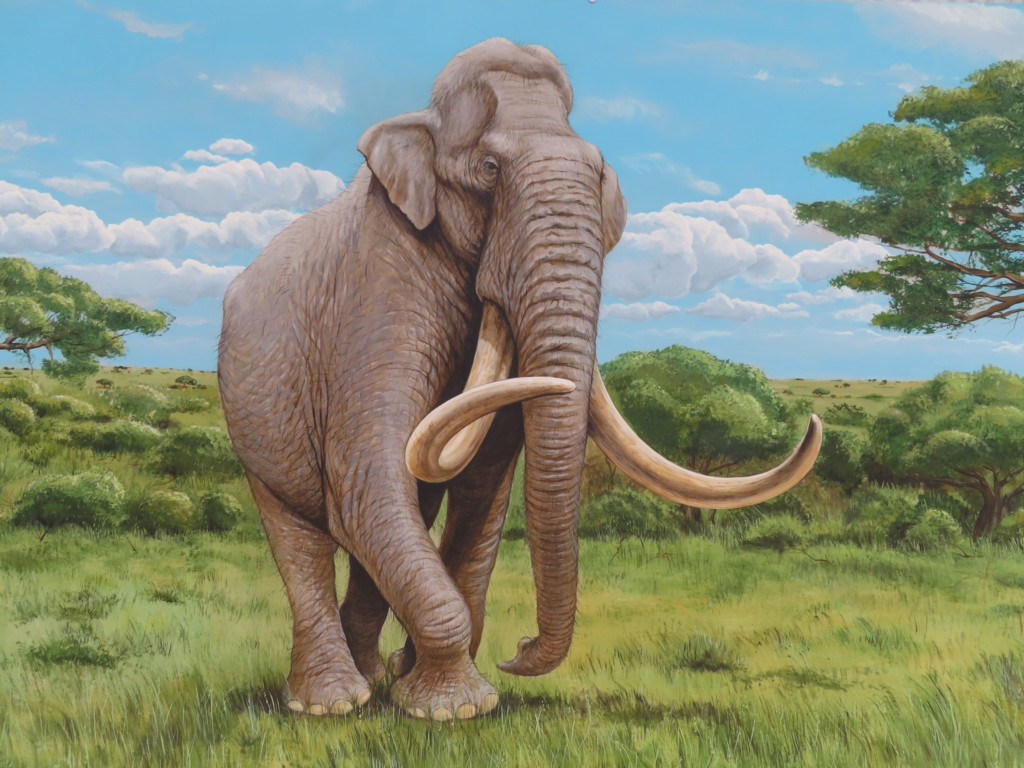

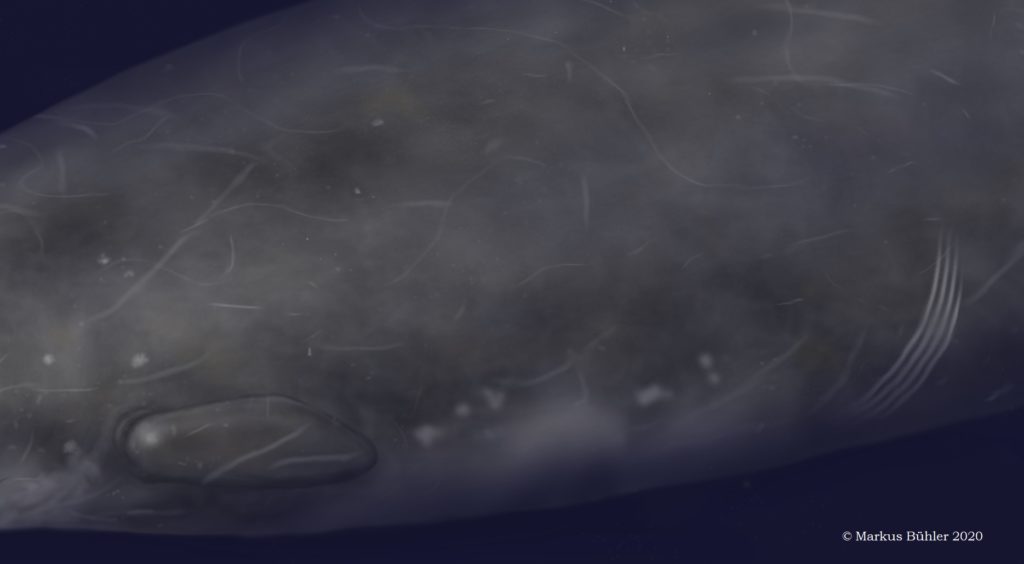

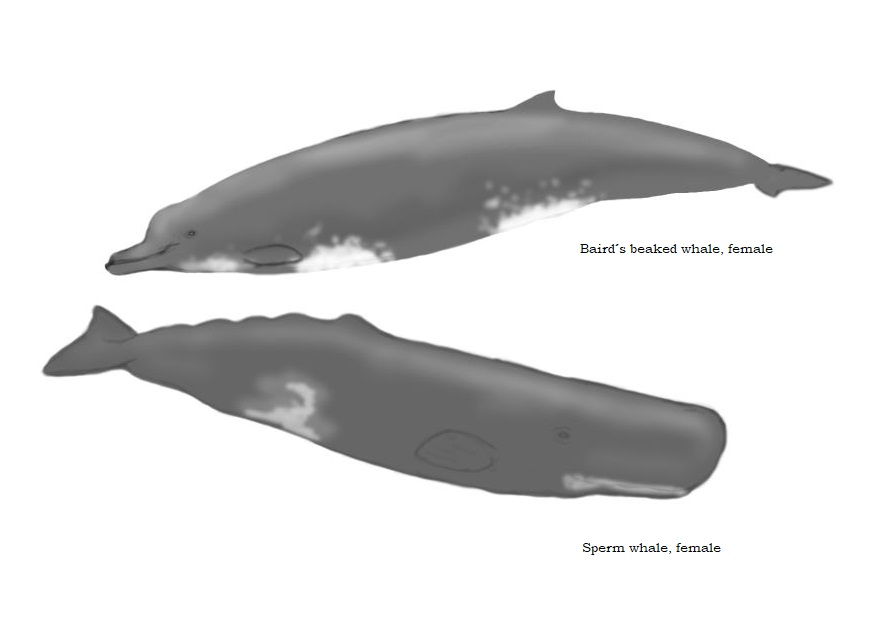

I have to admit that I usually mainly dismissed them as well, until I realized what incredible and fascinating creatures they are. First of all they are big, the largest beaked whales of the northern Atlantic and overlap in their size ranges with orcas. Exceptionally arge bulls can grow to 9,2 m or possibly even 9,8 length and close to 10 tons in weight, what’s about two times as heavy as an elephant or similar to the biggest orcas. The average sizes are of course lower, but it is not that easy to find good size data for the averages of this species. But even then we have a predatory cetacean in the waters of the northern Atlantic which grows regularly as heavy as a big African elephant bull. The possibly most prominent trait of the northern bottlenose whale is its melon. It is rounded and markedly set off the beak. It is more pronounced in males than in females and it continues to increase in size for a very long time. In old bulls it can reach grotesque dimensions and forms a protruding steep ram-like shape, which overtowers the rest of the head, similar to the over-dimensional spermaceti organ of old sperm whale bulls.

The ontogenetic changes are very strongly pronounced and old bulls differ significantly from younger – also already fully sexually mature bulls. They are much bulkier, have huge domed spermaceti organs with corresponding enlarged cranial structures below, often distinct whitish facial areas and grow also a pair of mandibular teeth which are also used for intraspecific fights. I like to call such old males with extreme morphological features which make them highly distinct from normal males „veteran bulls“. We find similar cases in certain other species as well, for example sperm whales, elephants, bears, wild boars, giraffes or even apes. This really is a topic of itself, and I hope to write more about it anytime in the future. In many beaked whales the tusks are mainly used for fights, but in Hyperoodon the huge enlarged heads are used like battering rams.

It is really unusual for mammals that teeth erupt only in older males long after reaching sexual maturity. In Hyperoodon they erupt at an age of about 15-17 years. In many other beaked whales and some other odontocetes we see a lot of scars from intraspecific confrontations, sometimes at massive degrees. In comparison the amount of scaring in bottlenose whales appears very moderate.

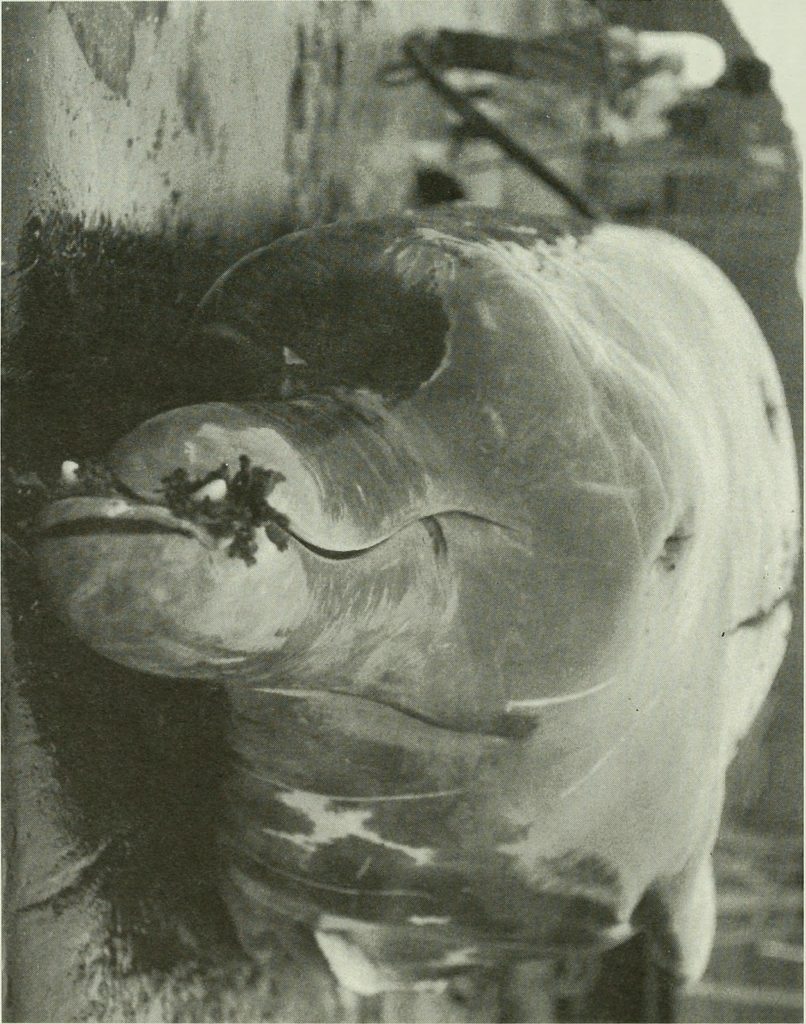

Here is a detail photo of the teeth from the skeleton above:

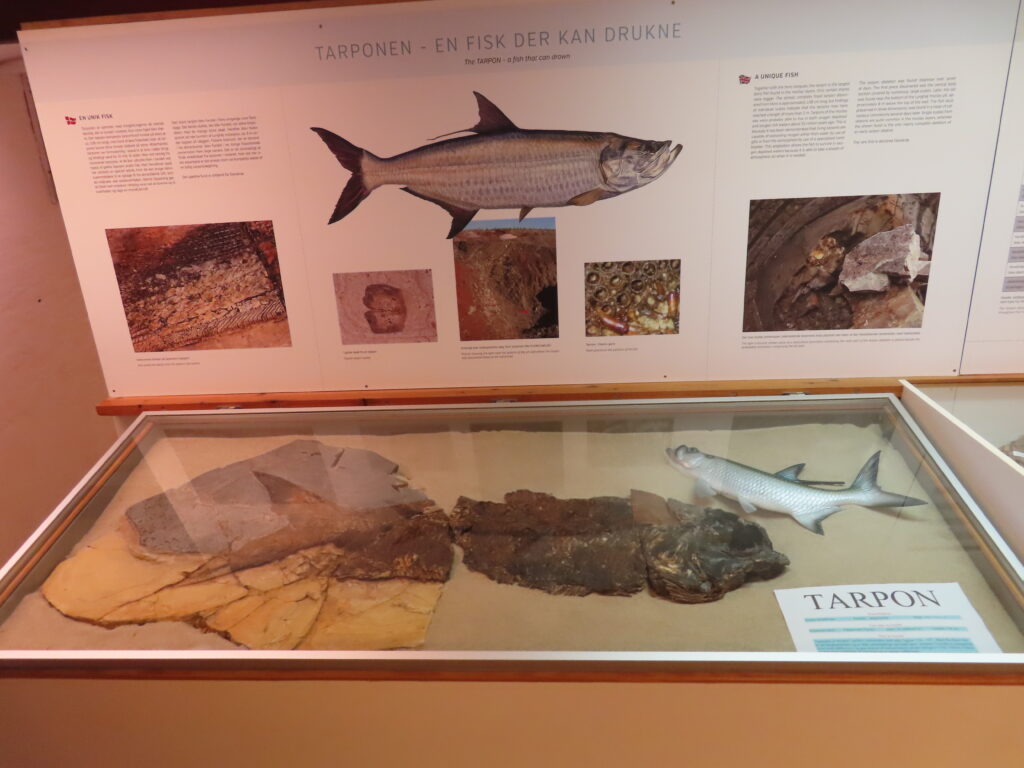

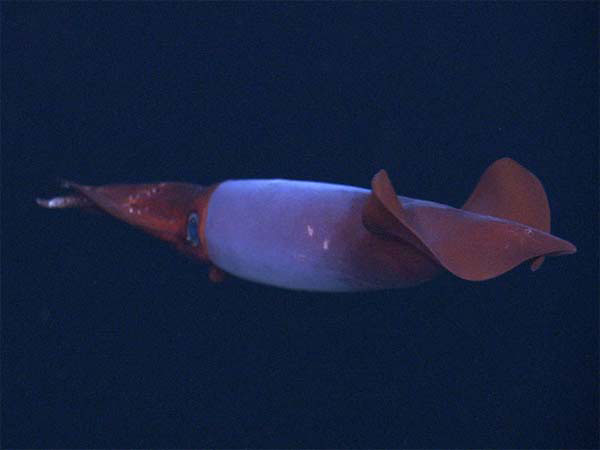

Like in most other beaked whales (Sheperd’s beaked whale might be an exception) teeth play no important role for hunting and prey is caught by suction feeding. Most of their prey consits of small to medium-sized squids and fishes. The squid Gonatus fabticii is a particularly common prey species in the North Atlantic, which reaches a mantle length of about 30 cm. Most surprisingly however is the occasional consumption of echinoderms like starfish and sea cucumbers.

This is really unusual given the fact that few marine animals feed at all on those invertebrates. But a giant cetacean which eats benthic echinoderms is truly amazing. Bottlenose whales are among the deepest diving cetaceans and regularly swim down to depths of more than 1000 m, with a record depth of even 2339 m. They can stay underwater for at least one and a half hours what’s among the longest diving times among mammals.

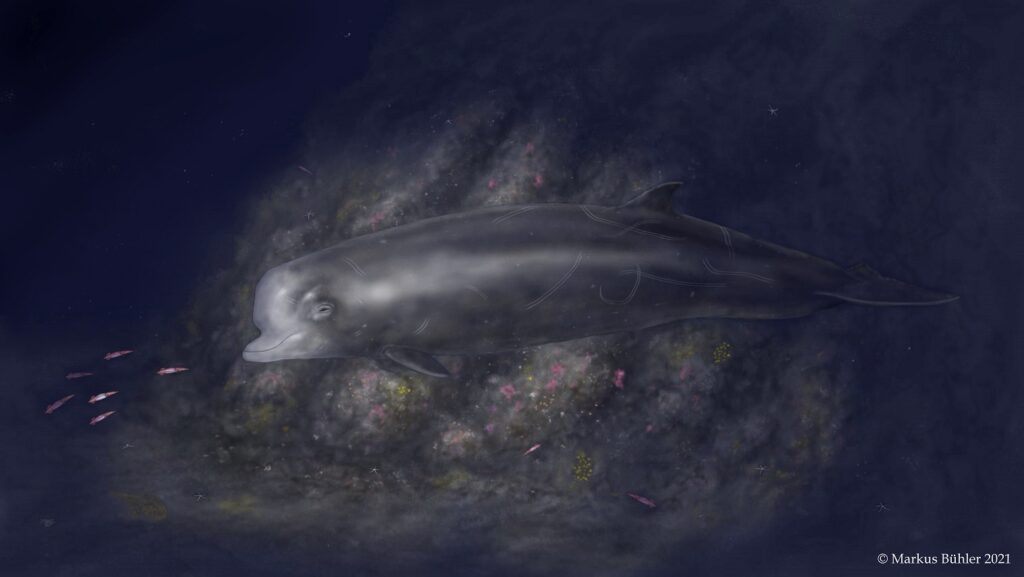

I think it is really important to see those whales as some kind of travelers between two worlds. We can only see and observe them when they are near the surface, but they spend much of their lives in abysmal depths, within a completely different environment. They interact with an ecosystem which is still very alien and little known to us. And they are not just mere spectators of that world like humans in a submarine but active elements of this deep sea ecosystems. After all, they are likely even very important parts of this environmental network, the second largest predators in the depths of the Atlantic ocean. A small group of bottlenose whales already consumes a similar amount of fish and cephalopods as a sperm whale bull, and this on a daily basis.

That’s why I tried to give you an impression about this world in the depths of the northern Atlantic ocean. The landscape is sometimes truly spectacular with deep canyons and elevations. The invertebrate fauna in this lightless areas is also surprisingly colorful and can even compete with the shallow reefs of the subtropical seas. One of my references was the Gully Canyon which is located east of Nova Scotia, close to the edge of the continental shelf of North America. This enormous deep see canyon has a length of over 65 km and is up to 16 km wide, with a depth up to 1000 meters. If you look for pictures you will find some spectacular photos which show the unexpected colorfulness of this part of the ocean which has never seen a glimpse of sunlight. I wanted to show you how this hidden world deep below the surface of the Atlantic ocean looks like, and how its second largest predator patrols the depths in search of squids, fish and echinoderms.

The inspiration to illustrate a deep-diving cetacean within an underwater canyon landscape goes back to my good friend Cameron McCormick.

References:

Ellis, R. (1996). Deep Atlantic. Knopf.

Nowak, R.M. and Walker, E.P. (2003). Walker’s marine mammals of the world. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

?