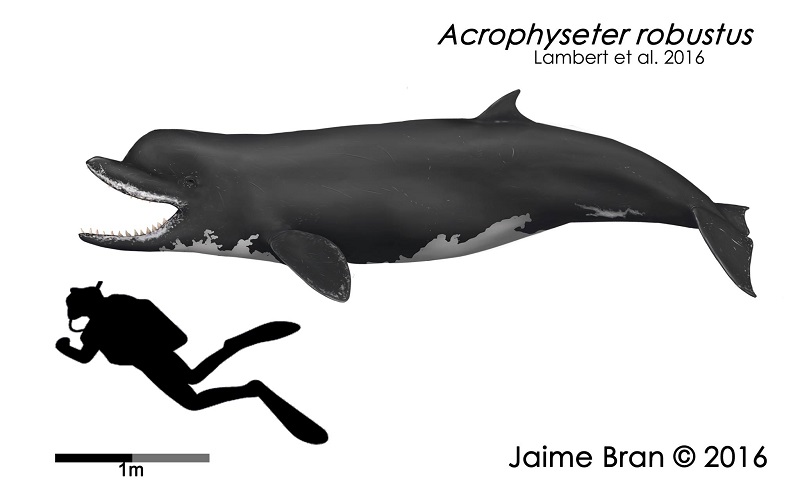

As I already wrote a in an earlier blogpost, archaeocetes were most probably not the skull-headed pseudo-reptilian horrors as which they have been usually depicted since Basilosaurus was discovered in the first half of the 19th century. Sadly this trend is still going on, and even today archeocetes are commonly shown without any cheek-, lip-or nasal soft tissue and with unnaturally skinny necks.

Besides this, there is also another feature of archaeocetes, which has been nearly fully forgotten over all the years, the likely presence of short bristles or hairs on the snout and chin area.

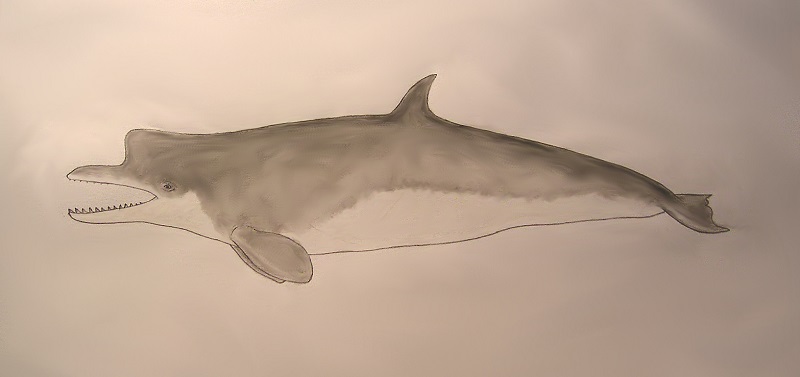

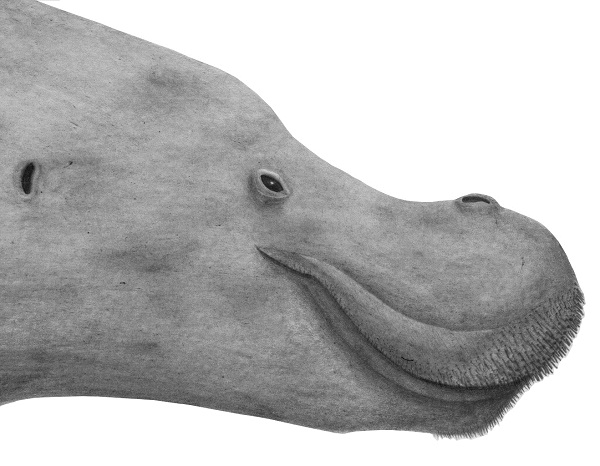

What, archaeocetes with bearded faces? As strange as it may sound at first, there are actully good reasons why early whales had quite probably some sort of facial hair. Here is a modified version of my earlier reconstruction of Dorudon atrox to give you an idea how this could have looked:

Dorudon atrox with vibrissae by Markus Bühler

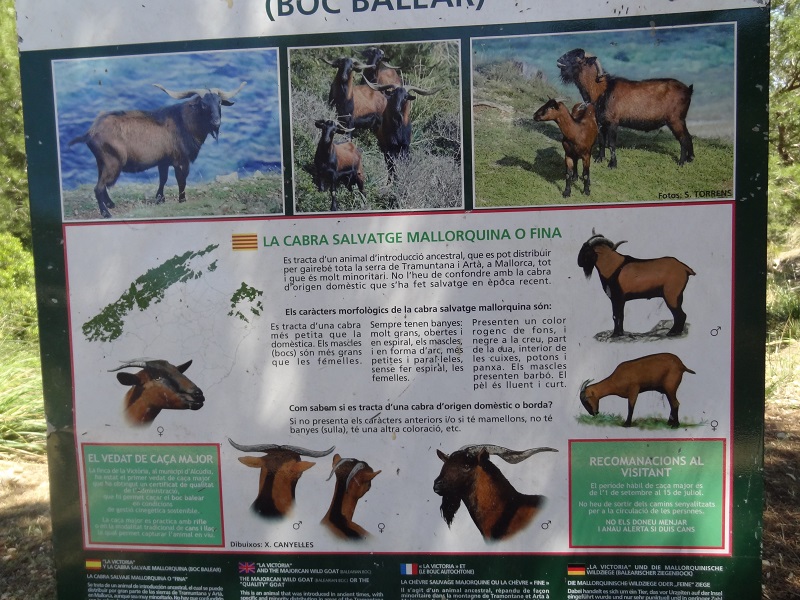

The idea to write a blog-post about archaeocetes with facial hair started when Nic Grabow asked me some time ago for my opinion about a more unconventional reconstruction of Basilosaurus he did, which included several quite „terrestrial“ traits like some sparse body hair, extensive facial soft tissue and short bristles on the upper lips and snout.

Basilosaurus with bristly snout by Nic Grabow

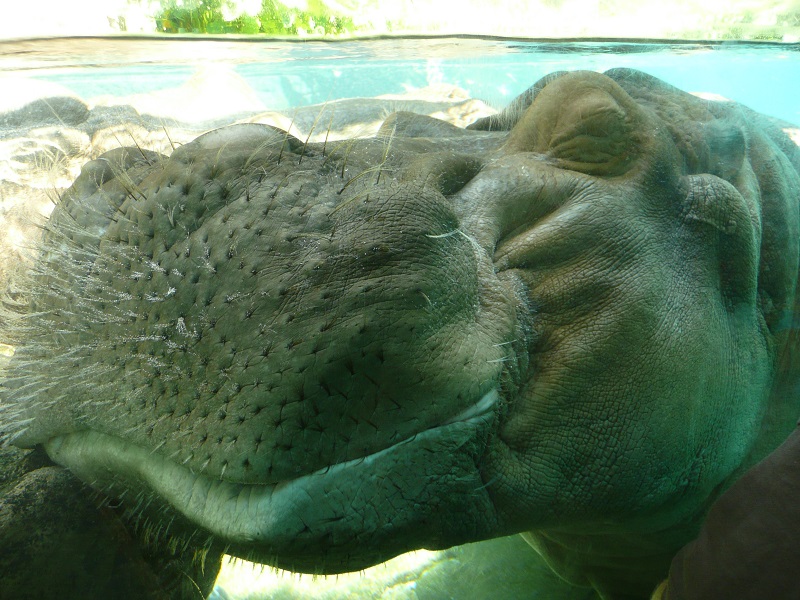

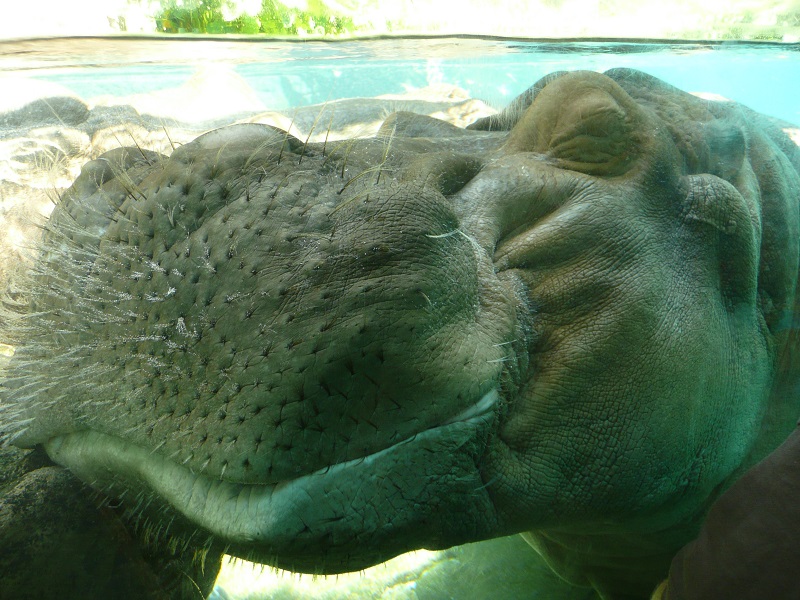

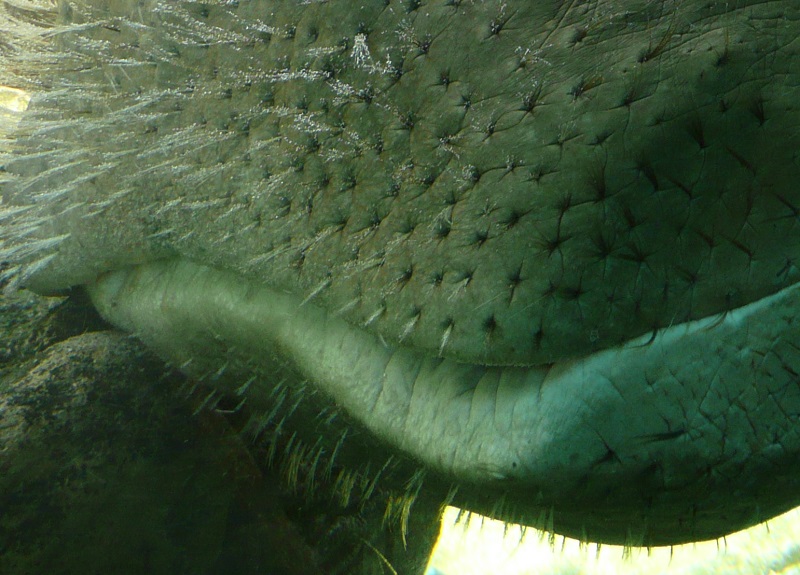

Whales evolved from archaic ungulates, animals which were originally still fully covered in fur. Their closest modern relatives, hippos and pygmy hippos, have only an extremely sparse vestige of the body hair of their ancestors, with only a few isolated hairs covering their skin. Their fleshy lips, the area below the nostrils and the chin are however still densely covered with short bristle-like hairs.

Hippo mouth closeup, photo from Wikimedia Commons

Carnivores like cats for example, have often quite noticeable whiskers, which are much longer and thicker than the other hairs. Seals in particular, which rely highly on the mechanoreceptive function of their vibrissae, have often very impressive whiskers. The longest vibrissae are found in the Anarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazella), with a record of 48 cm for the longest single vibrisse known (more about pinnipeds vibrissae in this older blogpost). In ungulates however, those vibrissae are normally much lesser noticeable, shorter and thinner. Interestingly they are often also comparably numerous below the lower lips in the chin area, as can be seen on this close-up of the mouth of a yak. Another example which shows very well the vibrissae of a deer can be seen here.

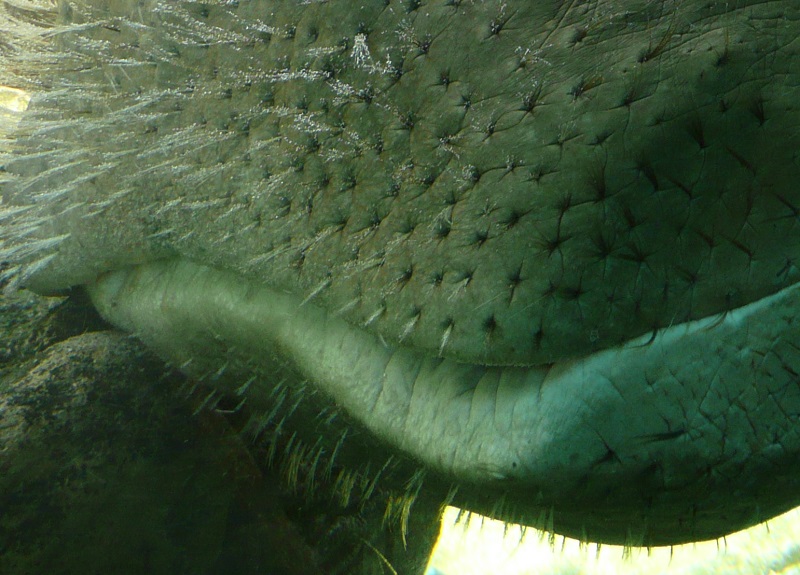

Here is a nice photo which was taken by a friend of me several years ago at the Zoo of San Diego. You can see the fine stiff vibrissae very well:

Hippo vibrissae, San Diego Zoo, photo taken by Jan Haas

Each of those hairs grows out of a small foveola in the skin. Vibrissae are different from normal hairs and have a tactile function. The large follicles of the vibrissae include a special capsule of blood, a so-called blood sinus. It is very well innervated and has together with the embedded hair a mechanocereptive function.

Now what´s really interesting is that vibrissae are also found in some whales as well. Right whales for example have quite numerous short vibrissae on the middle of their upper lip and more broadly on the lower lips, in a quite similar arrangement as those of hippos. Furthermore, bowhead whales have also around 10 vibrissae behind the blowhole.

North Atlantic right whale from Wikimedia Commons

Each of the around 250-300 vibrissae is situated in a small pit in the skin.

Here is another photo of right whale vibrissae.

In gray whales, which mainly feed on invertebrates which they sieve out of the sediments, the head is also covered with a lot of sensory pits and fine vibrissae. A nice photo which shows those hairs can be seen here.

The weird turberles along the rostrum and lower jaw of the humpback whale are also highly innervated modified vibrissae.

Humpback whale head with tubercles. Source Wikimedia Commons

You can see the fine hairs in the centre of the tubercles here. The exact purpose of those tubercles is still not fully known, but they act quite probably as sensory organs, perhaps connected with the unusual feeding behavior of humpback whales or for social interaction. A role for swimming was also suggested.

It is quite interesting that numerous and sometimes highly derived vibrissae are still found in modern baleen whales, even among very different families with very different feeding behaviors like mainly microplanctivorous right whales, krill- and fish-eating rorquals and bottomfeeding invertebrate-eating gray whales. It is likely that those vibrissae have more than just a single function, and assist not only during hunting and feeding, but also for social contacts with other whales and perhaps also for swimming.

Given the fact that baleen whales lack the highly derived echolaction of modern odontocetes and have also only limited eyesight, it is even possible that those vibrissae could even have a much more important role for food gathering than usually assumed. How do they find their prey? They clearly doesn´t just open their mouths anywhere on spec in hope of getting something to eat. Especially those baleen whales like humpback whales, minke whales or sei whales which feed also on fish (in some cases even on surprisingly large ones), have to target their prey items specifically, even if they are swimming in swarms. It was just recently discovered that rorquals possess a unique sensory organ in the area of the mandibular symphysis, which is also just the area where their mandibular vibrisae are located. This already leads to another highly complex topic, so I´ll make a break here.

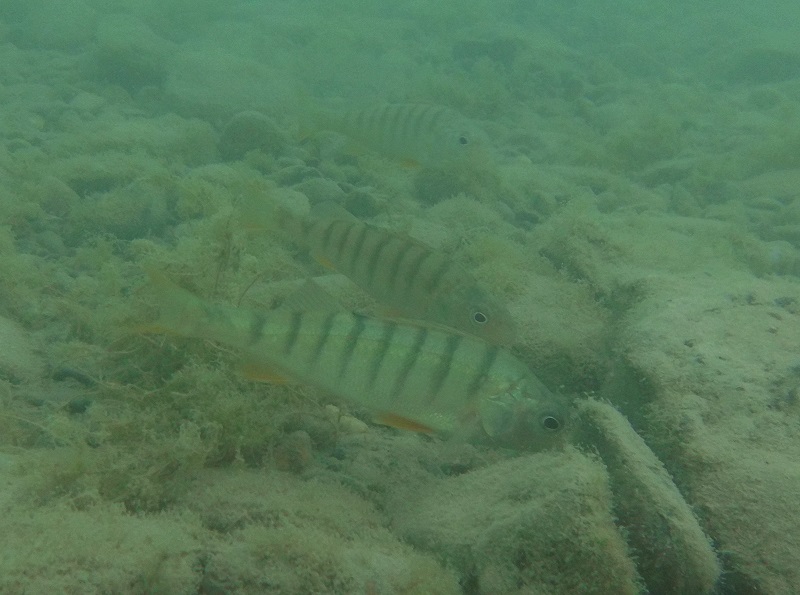

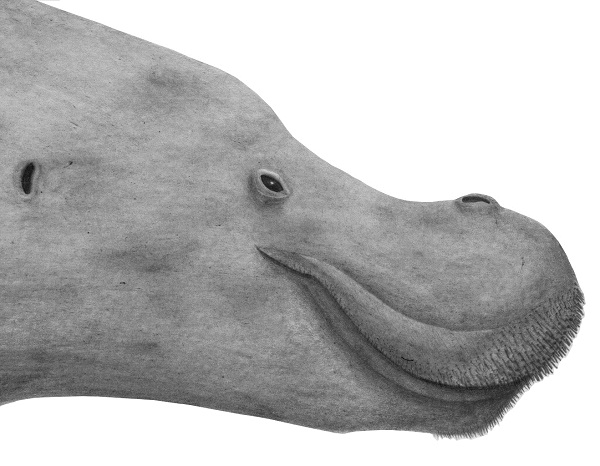

As we´ve seen, vibrissae are pretty common in baleen whales. But what about odontocetes? They seem to play a much lesser important role in most modern toothed whales, most probably because they rely mainly on echolocation. An exception are the Amazon river dolphins of the genus Inia, which have very well developed short bristles on their elongated jaws.

Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), Source Wikimedia Commons

Here is also a close-up photo of an Amazon river dolphin with bristles. This bristles are most probably an adaption for the often quite tanine-rich and murky waters in which those freshwater dolphins are living. In contrast to the true vibrissae of the baleen whales, the bristles on the snout of the Amazon river dolphins lack a blood sinus, but have also a highly enervated follicle. Vibrissae are found in other odontocetes as well, but they are usually shed prenatally or shortly after birth. The follicles however remain, and can persit as so called hair-pits or vibrissal crypts, which were shown in Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) to act as functional electrosensitive organs.

So given the fact that the terrestrial and semiaquatic ungulate ancestors of modern whales surely had vibrissae, and vibrissae are still found in modern whales, especially those which have no echolocation, it seems highly probable that archaeocetes had functional and noticeable vibrissae as well. They were quite probably not as derived as the tubercles of the humpback whale or the vibrissal crypts or certain odontocetes. As those archaic predatory whales still had no echolocation and probably also didn´t just rely on eyesight underwater, it would make sense if their vibrissae were still well developed. Of course it is really hard to say how numerous or noticeable they were. Perhaps somewhere between those of a hippo and those of baleen whales and Amazon river dolphins.

I depicted my updated version of Dorudon with vibrissae on the forepart of the mandible and upper jaw, plus some isolated vibrissae behind the nostrils. It is however also well possible that they extended from the whole area of the rostrum up to the nostrils, and that this reconstruction of a bearded archaeocete is even still too subtle. Perhaps they had even such noticeable vibrissae as modern hippos, what would have given them an even more unfamiliar appearance.

It seems after all much more likely that archaeocetes had still visible vibrissae than they had none. One of the earliest depictions of an archaeocete with extensive bristles was made by my good friend Cameron McCormick, who made this really interesting reconstruction drawing of the bizarre protocetid Makaracetus bidens with extensive lips and manatee-styled bristles.

Makaracetus bidens reconstruction with fleshy lips and vibrissae by Cameron McCormick

Makaracetus was most probably a durophagous molluscivore, which fed mainly on shellfish. Extensive mechanosensitive vibrisae on its lips and chin, comparable to those of walruses, seems quite likely for an animal which found its prey items mainly on or within the sediments of the coastal seafloor. This could also apply for the small archaic baleen whale Mammalodon.

There is also an old reconstruction model of the super-weird delphinoid Odobenocetops peruvianus with extensively bristled lips in a paper by Christian de Muizon from 1993. As Odobenocetops was an extremely specialized bottom feeding molluscivore, it seems not unplausible that it really had vibrissae on its lips, but more derived organs like vibrissal crypts could be equally likely.

Right down the line, it seems really justified to depict archaeocetes not just with more extensive facial soft tissue, but with more or less noticeable vibrissae as well. The depiction of „bearded“ archaeocetes would be of course nowhere as revolutionairy as for example those of feathered theropods, but it would still affect the way in which we would look at those fascinating forerunners of modern whales.

References:

Czech, N. (2007) Functional morphology and postnatal transformation of vibrissal crypts in toothed whales (odontoceti). Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Universitätsbibliothek

Drake. SE. (2015) Sensory Hairs in the Bowhead Whale, Balaena mysticetus (Cetacea, Mammalia). THE ANATOMICAL RECORD 298:1327–1335

Pyenson, N. D., J. A. Goldbogen, A. W. Vogl, G. Szathmary, R. L. Drake and R. E. Shadwick. 2012. Discovery of a sensory organ that coordinates lunge-feeding in rorqual whales. Nature 485: 498-501. doi: 10.1038/nature11135

Czech-Damal, N.U., Liebschner, A., Miersch, L., Klauer, G., Hanke, F.D., Marshall, C.D., Dehnhardt, G., and Hanke, W. 2011. Electroreception in the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis). Proceeding of the Royal Society B, doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1127

Dolphin Communication and Cognition: Past, Present, and Future. Denise L. Herzing and Christine M. Johnson, eds. 2015. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 328

Marine mammal physiology : requisites for ocean living / edited by Michael A. Castellini, Graduate School, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, USA, Jo-Ann Mellish, North Pacific Research Board, Anchorage, Alaska, USA