This blog is devoted to the wonders and marvels of the animal kingdom and natural history. Many of the photos in my articles were taken in zoological or paleontological museums. But you can also often find a lot of really interesting zoology-related artifacts in other museums as well. I have a longstanding interest in archeology, history and ethnology, and for that reason I visited countless museums about those fields over the years.

I have seen there innumerable and sometimes really surprising exhibits which can be also of great value for people interested in zoology. Not everyone can spend several hours analyzing the construction of ancient arms and armor or the carving techniques of old wooden spoons as I sometimes do. But even if you are not really an avid fan of archeological, historical or ethnological museums but interested in animals (I suppose you are, otherwise you would not read my blog), I can encourage you to take a closer look at those locations. I think I can not emphasize enough the potential of such collections, and sometimes you can even find amazing and fully unexpected zoological treasures that you will rarely find even in natural history museums.

The vestigal narwhal tusk featured recently is such a case. The Inuit tools made from the teeth of Greenland sharks were the very relics of Somniosus I have seen anywhere. Another example would be the mandible of a pygmy sperm whale in the Oceania exhibition of the ethnological museum at Berlin (I already wrote about it several years ago here).

Pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) mandible, Ethnological Museum Berlin

The mandible was sadly labeled as the jaw of a dolphin. I tried to contact the museum to inform them about the true identity and rarity of this mandible, which belongs to a species which is really rare even in the collections and archives of museums with many cetacean specimens. Sadly I received no answer.

This leads to another thing. This is really not meant to discredit the scientists, curators or the staff of those museums, but over the years I have seen a whole lot of erroneously labeled exhibits in archeological, historical and ethnological exhibitions. For this reason it can be really beneficial if people with a more profound knowledge of zoology take a closer look at them. Of course no one likes a smartass (ans yes, I am fully aware of my strong tendency to be one), but museums have an educational purpose and labels should be corrected if they are erroneous. At the end, that’s also beneficial for those museum and their visitors, in particular if a „boring“ object becomes suddenly much more interesting.

This is even more important if erroneous identifications lead to erroneous interpretations, what’s especially problematic in the archeological context. I hope to feature such a case in the near future.

But enough with the criticism, in the vast majority of cases the identifications of animals in such museums are correct, an you can learn a lot from them.

Real physical remains of animals are of course especially interesting, the more so if they belong to unusual or now extinct species. I have seen many subfossil aurochs skulls and horn cores, and even some full skeletons, and a great number of them in archeological museums. This included even a particularly spectacular (perhaps even the most spectacular) specimen which I will spare for a future blog post. So if you are a fan of Bos primigenius, you can likely expand your specimen count in archeological museums to a substantial degree.

Aurochs (Bos primigenius) horn cores (on the top) in the archeological museum Strasbourg. Did you notice the warthog model?

But even the skeletal relics of lesser uncommon animals are always worth to take a closer look at them, no matter if they are wild or domestic animals. Sometimes you will also see bones of animals which are now extinct in the area where their relics were found, like Central European mooses. Some animals which greatly suffered from trophy hunting over many centuries have also often decreased in size. For that reason you can often find especially massive deer antlers or huge wild boar tusks which come from archeological excavations or which are from historical hunting collections.

A huge neolithic wild boar skull with enormous tusks from the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen

Ethnological collections are sometimes real treasure chests, as they often include really exotic animal remains. Anatomy, behavior and ecology of animals are all fascinating things, but I think the interaction of animals with humans are always important to look at as well. The cultural or economic role or value of animals, the way in which they were hunted or caught or what was made from them. This are all really interesting topics of themselves, but they often get not that much attention in zoological museums.

Necklace made from hornbill beaks, likely from New Guinea. How often can you take such a good look at the inside of their mandibles? Photo taken at the Ethnological Museum Munich

You are sometimes really surprised by the weird hunting methods invented for certain species or the curios use of certain animal parts. Sometimes such processed body parts can give you even insights into anatomy that you will usually not see at a taxidermy specimen or a mounted skeleton.

A very nice collection of Crocodylus porosus skulls and boar skulls. Ethnological Museum Munich

In exhibitions about Oceania you will often find especially many artifacts made from animals.

Necklace made from sperm whale teeth. This gives you a pretty good idea about the variation in shape of sperm whale teeth. The big blunt tooth is quite interesting, as it shows severe abrasion. Photo taken at the Ethnological Museum Berlin

Native American artifacts can be also very interesting, for example if they give you a chance to take a close look at bison skulls.

Bison skull with painted ornaments, Ethnological museum Berlin

But not just physical remains can be valuable objects of interest, but artistic animal depictions as well. In some cases they can tell you things about now extinct animals that you can’t see if you just look at their bare bones. Colours, patterns, even certain typical kinds of behavior and interaction with other animals and humans can be found in ancient art or historical depictions.

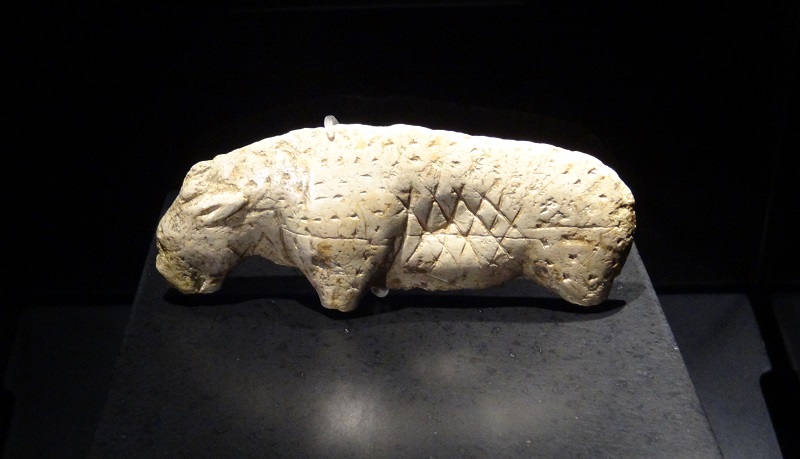

Mammoth ivory figurine of a cave lion from Vogelherd Cave at Schloss Hohentübingen. Could the pattern carved on the body indicate that some cave lions had more or less pronounced spots?

One especially worthy field to discover in archeological museums are old forms of domestic animals. You can for example look which unusual traits typical for domestication were already present. You can take a look at ear shape, length or structure of the fur, the pattern and colour of the hides or other traits you can not judge from skeletal remains alone. Many old breeds of domestic animals became fully extinct, others changed so much that they bear no more much similarities with their ancestral forms.

A greek bronze helmet from 300-400 BC. The engraving of the bull is just wonderful and incredibly naturalistic. It reminds a lot on a Spanish fighting bull.

A small roman bronze figurine of a domestic bull with strongly developed dewlap.

Roman bronze bull, Landesmuseum Stuttgart

Terracota model of a South American dog breed. This small, short-legged dogs had strongly wrinkled skin and were bred for their meat.

Ethnological museum Berlin

Domestic dogs were already quite diverse in antiquity, and very different breeds already existed millenia ago.

A greyhound-like breed of dog on a Greek amphore, ca 440 BC. Photo taken at Landesmuseum Stuttgart

You can for example see typical traits of domestication in some of those old breeds, like floppy ears of a curled tail.

Dog with floppy ears and curled tail on Greek amphore, 480-470 BC, Antikensamlung Berlin

A very nice life-sized sculpture of a hunting dog from ancient Greek. This is in fact a cast from gypsum and not the original.

Greek hunting dog, Schloss Hohentübingen

Of course you always have to keep in mind that there can be a lot of artistic freedom in such old depictions. Sometimes more, sometimes lesser. But to get a better idea and understanding of that, it is important to study the various art styles of different cultures. In some cases you will be really surprised by the level of accuracy of those ancient artists. Some of the ancient Egyptian paintings and reliefs are so naturalistic that it is easy to identify even a lot of animals to species level.

On occasion you will even see quite unexpected scenes of human-animal interaction, like apparent attempts to tame wild animals. It is also sometimes really surprising to see the degree of human translocation of animals which happened already hundreds or thousands of years ago.

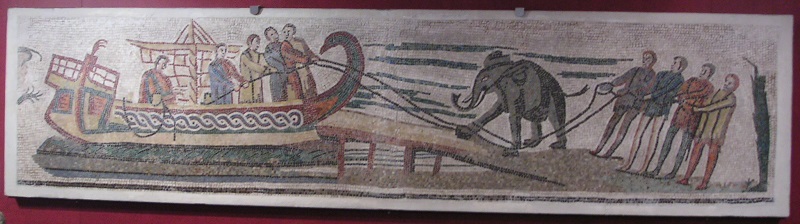

How to transport an elephant on a ship, Roman mosaik from Veji, 300-400 AD, Landesmuseum Karlsruhe

The depicted elephant was most likely the now extinct small North African subspecies Loxodonta africana pharaohensis.

You can also sometimes see unusual curiosities from historical collections, like anomalous antlers, horns or tusks, or bezoars which were thought to have healing powers, similar to the inevitable narwhal tusks. In other cases there are very early examples of exotic animals or animal parts which found their ways into cabinets of curiosities or early zoological collections. You will find such collections much more often in historical than zoological museums, and they can give you interesting insights into the history of modern zoology.

Bird of paradise in historic cabinet of curiosities, Landesmuseum Karlsruhe

Here you can also see a wonderful mug made from narwhal tusk. You can see that was from the base of the tusk, as the surface is unabraded and highly textured.

Narwhal tusk mug, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

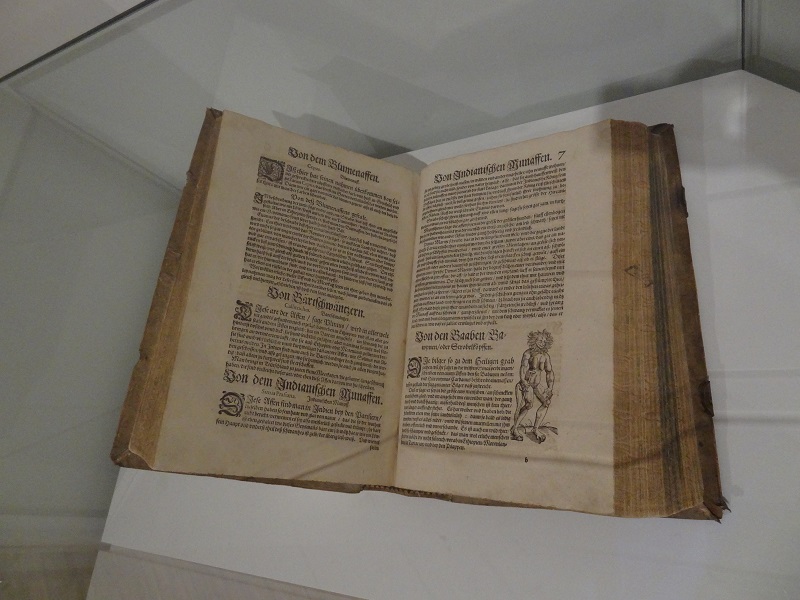

An original copy of Conrad Gessner´s (1516-1565) Historia animalium, one of the very first zoological books of the world. The same exhibition also had an original print of Dürer´s Rhinoceros.

Historia animalium by Conrad Gessner, photo taken at a special exhibition at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

I hope I could show you with this blogpost why it can be always worthy to think outside the box, and to visit as many museums as you can, even if they are not always restricted to natural history alone.

I like reading your blogs. It´s interesting. But only one thing in this one – there is wrong latin name below first photograph. It´s not Koga but Kogia. Just a little thing. 😉

Oh thanks, this was of course a typo. This was a really extensive post to write, and even if I re-read it for several times, it can happen that I just miss even such obvious typos or grammar errors. In the original post where I wrote more about pygmy sperm whales, I used the correct name. Pygmy and dwarf sperm whales are really fascinating animals, and there are also some fossil forms on record, about which I wanted to write anytime too.