I have seen a whole lot of narwhal tusks in museums, many skulls of narwhals (Monodon monoceros), some fully mounted narwhal skeletons and even several specimens with double tusks. But so far I have never ever seen the vestigal right tusk of a narwhal somewhere on exhibit. Male narwhals have always two tusks, but in general, only the left one is noticable and protrudes out of the upper lip. The right tusks however usually remains embedded within the maxillary bone and normally never erupts. This tiny tusks are much smaller than the erupted tusks, and you can only see them if they are extracted out of the skull, or if the bone of a skull is already damaged. So far the very only vestigal narwhal tusk I had seen was one which was still embedded into a the broken bone of a skull I have seen at the archive of the Zoological Museum at Copenhagen. But much of it was still hidden under bone.

So I was really highly astonished when I recently discovered such a specimen which was fully bare of bone. But it was not in a Zoological museum, but in the exhibtion of the Landesmuseum Württemberg at Stuttgart, a historical museum about archeology and the history of the territory of Württemberg. It includes a historic cabinet of art and curiosities, the Kunstkammer („art chamber“), which dates back to the late 16th century. The tusk is a loan from the Natural History Museum at Stuttgart, probably as some sort of surrogate for a big narwhal tusk, which would not have fitted into the showcase. It was also only labeled as „narwhal tusk“, without any additional information about its unusual nature, but the old-fashioned hand-written labels indicates that it is not of modern origin.

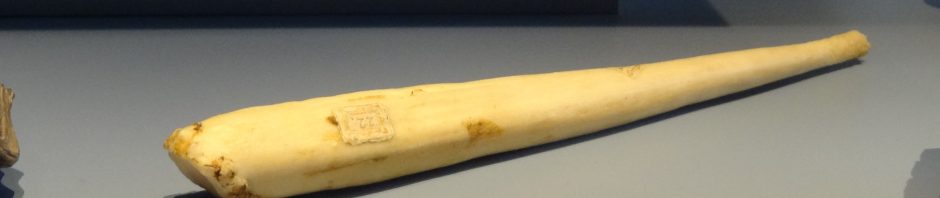

Vestigal right narwhal tusk, Kunstkammer Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

As you can see, the shape differs a lot from those of the iconic „unicorn“ tusks. It fully lacks the spiraling, which is so typical for the erupted tusks. But this one still seems to have some parallel grooves. It is also not fully straight, because it is not twisted. The erupted tusks are often not completely straight, but form a more or less pronounced corkskrew-shape. But they always follow a nearly perfect straight line around their centre, as the spiraling of the tusks prevents them from growing in a curve.

The tip is also very thin and not pointed. If the big tusks erupt, they are also very pointed at first, but abrade their tips over time. At the next photo you can also see a detail in which it differes from the big tusks. Its foramen apicale, the apical opening of the tooth which connects the pulp with the blood vessels and nerves of the surrounding bone, is only very small. In the big tusks it is fully open, and about the diameter of the whole tooth. This is the area where dentine and cementum are produced and where the tusks continuously grows. The pulp gets its nutrution over the blood vessels which enter the foramen apicale, and here is also the interaction of the sensory nerves with the tusk. But the small vestigal tusks don´t need to grow anymore, nor do they need much nutrition or have any more sensory function, so the apical formanen is nearly closed.

Foramen apicale of a vestigal right narwhal tusk, Kunstkammer Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

You can also see that it has a very clean colour, unlike the yellowish erupted tusks, that have often dark veined spiral grooves. This colour comes from algae, diatoms and various particles from the surrounding water and sediments, which can stain the narwhal tusks like coffee does on human teeth.

The unerupted right tusks are also quite variable in shape, as they have nearly no more selection pressure. That is similar to human wisdom teeth, which also show a massive amount of variation, and which can be also vestigal with reduced sizes or aberant shapes of the crowns and roots.

Here is also a photo which shows the tusk in the showcase, together with a number of toadstones (fossil teeth of Lepidotes), a fossil oyster from the Swabian Alps, an ammonite and a large fossil shark tooth:

Vestigal right tusk of a Narwhal, Kunstkammer Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

There are two embedded tusks in the skulls of female narwhales and one (the right one) in those of males.

Three of them are on my writing desk while I write this and I try to describe them:

Length ranges from 18 cm to 25 cm. Two of them slighly spiral counterclockwise

as the erupted tusks of males do.

Although there is no growth in length that leads to eruption (there are exceptions)

they show a development through lifetime – in young animals the foramen apicale is wide open with an explicit cavum pulpae. This closes bit by bit until you find an even

completely closed foramen and an „overproduction“ of dentin and cementum at the caudal end of the tusk.

A study from 2012 shows that the tusks of narwhales grow out of the maxilla.

That means they developed from canines during evolution and they are not incisors.

p.s. Sehr geehrter Herr Bühler, ich hätte gern noch ein paar Fotos dazu eingestellt,

wusste aber nicht ob und wie das geht.

Thanks for this additional information. There are also several other narwhal-related topics on which I had plans to write, including their assymetrical growth when both tusks erupts or their canine-origin, but also tusk fractures and certain anomalies. I had also already the pleasure to see the historic double-tusked skull from Hamburg, which also belonged to a female narwhal. This could be also an interesting topic for a blog-artice. I also wrote a blog-article about the possible evolutionairy history of narwhals many years ago, which I hope to update anytime with more illustrations. I have sadly also no idea how to include photos in the comment sections, so I cann´t sadly help you with this problem.