There is an enormous marine carnivore which grows as long as a bus, and most people are fully unaware of its very existence. Nearly everyone knows sperm whales, but if you would ask people about the world’s next largest extant predator (if we exclude baleen whales which are still carnivorous and sometimes surprisingly predatory), it’s very likely that a lot of people would struggle. Many would likely answer that orcas are the second largest carnivores, but this formidable predators are still not at the second range after sperm whales. In fact they aren’t even at the third range. I am sure that a lot of people would be very surprised to learn that there are besides sperm whales other predatory marine mammals larger than orcas in the world’s oceans. But hardly anyone could name them, and even those who know them are often not fully aware of their enormous size.

The name of this beast is Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii), sometimes also called the giant beaked whale. This little known leviathan is an inhabitant of the northern pacific ocean, whereas its slightly smaller antarctic sister species, the Arnoux‘ beaked whale (Berardius arnuxii), inhabits the circumpolar oceans of the southern hemisphere. Giant animals gain usually a lot of attention, even more so if they are predatory. Even children’s books are full of sperm whales, baleen whales, orcas, whale sharks or basking sharks and you can see them in countless documentaries. So how could it be that Berardius somehow evaded to get attention? Beaked whales are in general quite elusive and still among the least known big mammals of the world.

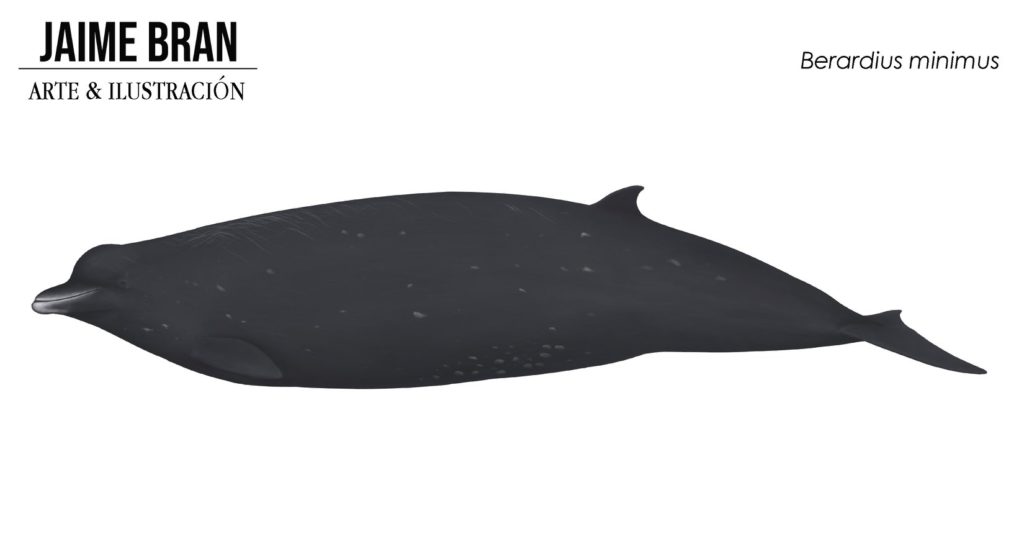

Even today some species are only known from a handful of specimens and we still know nearly nothing about much of their behavior. As late as 2019 a „new“ species of Berardius was described from Japanese waters, Berardius minimus (more about earlier implications for this new species at Lord Geekington). It had been known to Japanese whalers since a long time and was called kuro-tsuchi (meaning „black Baird´s beaked whale). In contrast to B. bairdii which is greyish with some white markings in the chest area, B. minimus is nearly fully jet-black. It also differs in its body proportions from Berardius bairdii, which occurs in the same area. B. minimus has also a stouter melon, a shorter and more compact body shape and a much smaller size, growing „only“ to about 6,9 meters. It also seems to suffer more from cookie cutter sharks than Berardius bairdii, as the known specimens showed a particularly large number of bite scars from this parasitic sharks. On the other hand the overall amount of battle scars from intraspecific fights appears considerably lesser than in B. bairdii. Here is a wonderful illustration of Berardius minimus by Jaime Bran:

Battle teeth and barnacle-plaque

Most beaked whales have a highly reduced yet also highly specialized dentition. Cephalopods and smaller fish are caught by suction feeding for which teeth are not necessary, especially as most prey items are very small. The pair of lateral throat grooves and the well-developed hyoid bone and muscles can create a strong vacuum to literally suck in prey. In general only the males have teeth, usually a single pair. Beaked whales of the genus Berardius however have four remaining teeth in the lower jaw which also erupt in both sexes, whereas the upper jaw is completely toothless.

The first pair is located at the top of the prognathic mandible and is functionally extraoral (narwhals are not the only cetaceans with such a condition, we see this also in many beaked whales) whereas the second pair of teeth remains hidden as long as the jaws are closed. Many thanks to Sally Evans who made some great photos of a Berardius arnuxii skull at the archives of the Natural history Museum in London for me.

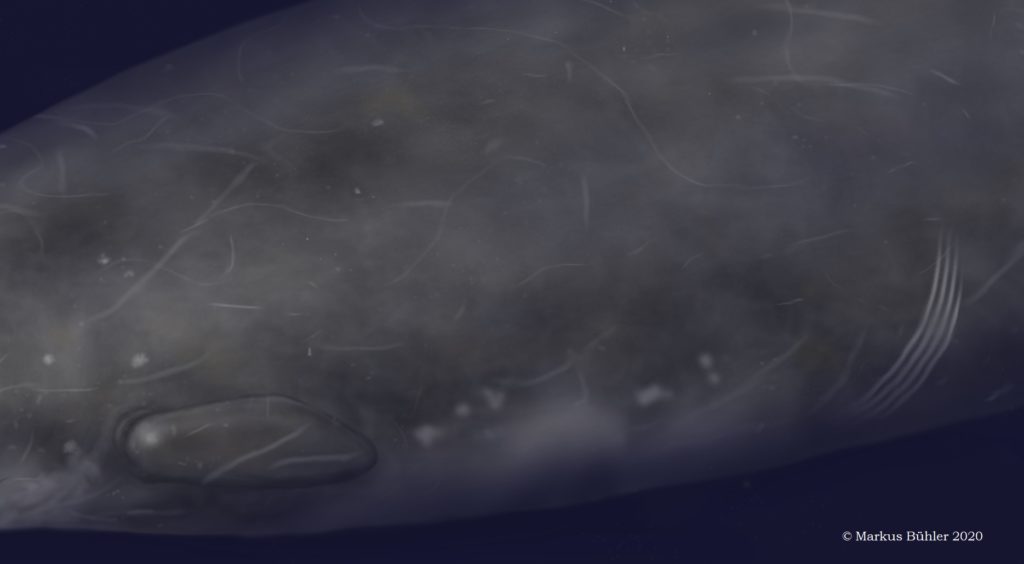

Those teeth are used during intraspecific fights and both males and females show scars from such confrontations. In some old males nearly the whole fore half of the back consists of scar tissue. Most of the scars were obviously caused by the first pair of the antagonist’s teeth, but sometimes you can also find four parallel lines of scars as well. I still wonder how exactly they manage to produce this kind of pattern. The parallel orientation of this scars means that the attacker scratched the skin either during a forward facing movement with widely open jaws or that it tried to bite the other whale and was moving backwards.

The teeth in dorsal detail view.

Adding scars to an animal is usually a fun part (much of the drawing and painting time is hard and exhausting work), it gives you the chance to give it some individuality and tell some stories of its life. But the amount of battle scars in Berardius is often of such an extreme extension over the body that I decided to depict it only with a very moderate amount of scars, like we see it in younger males. Too much white scar tissue makes it hard to see the original shape and anatomy of the body.

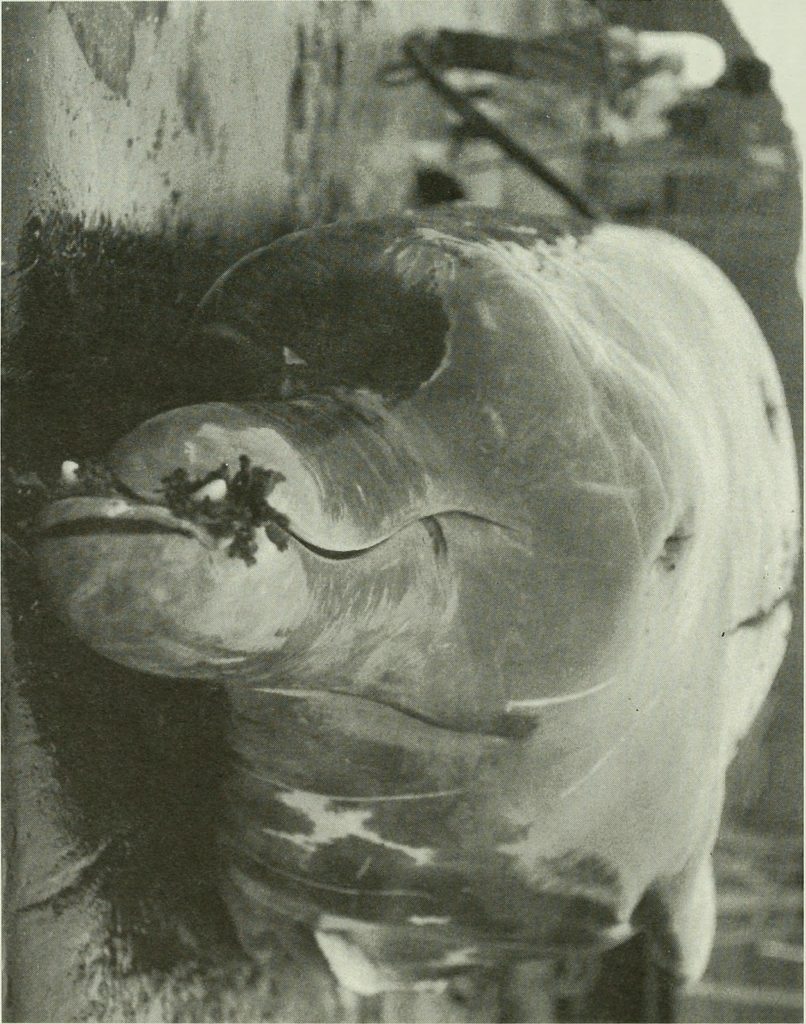

Due to the common use, the teeth they have also often strong abrasions in older individuals and can be worn down to the skin. Because those teeth are all the time surrounded by the sea, they get colonized by shell-less goose barnacles. This is a very common thing in beaked whales with extraoraly located teeth. In Berardius it’s mainly the marginal part of the teeth near the skin where the barnacles grow like a little brush. But sometimes the barnacles grow to quite considerable sizes, forming fleshy masses that look like kelp. You can see an example of excessive goose barnacle growth here.

The social life of Berardius is weird to say it at least, and could well be a chapter of its own. So I´ll refer here to Cameron McCormick´s excellent blog article which also deals with this topic.

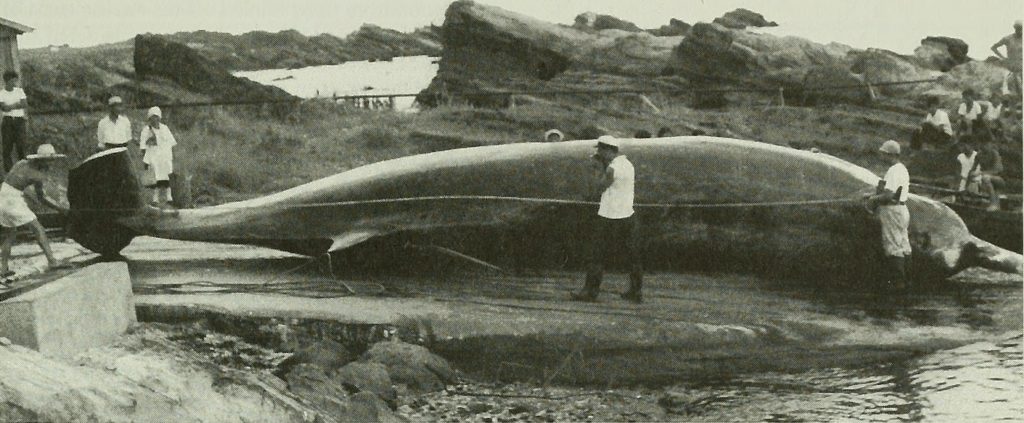

I wrote that Berardius minimus grows „only“ to about 7 meters. But how big is Berardius bairdii? The average is about 10-11 m, where males are somewhat smaller than females. The maximum recorded length for this species is 12,7 m and the maximum weight at around 10-15 tons. This is really enormous, bigger than every orca, and they range in a similar size class as the next biggest rorquals like the Bryde whale and Omura’s whale.

Arnoux´beaked whale is somewhat smaller but still reaches lengths of 9,75 m. As a result of the extreme sexual size dimorphism of Physeter the size range of Berardius even overlap with those of female sperm whales, and large Baird’s beaked whales are even longer than average-sized female sperm whales. Berardius bairdii also fills a similar ecological niche as Physeter and mainly feeds on cephalopods and fish in the deep sea. The main difference is that its diet does not include bigger prey species like large squids or sharks. But even sperm whales feed mainly on animals which’s are proportionally tiny and really large prey like adult giant squids are usually only consumed by males anyway. So it would be really interesting to know how much both species compete in areas where they are sympatric.

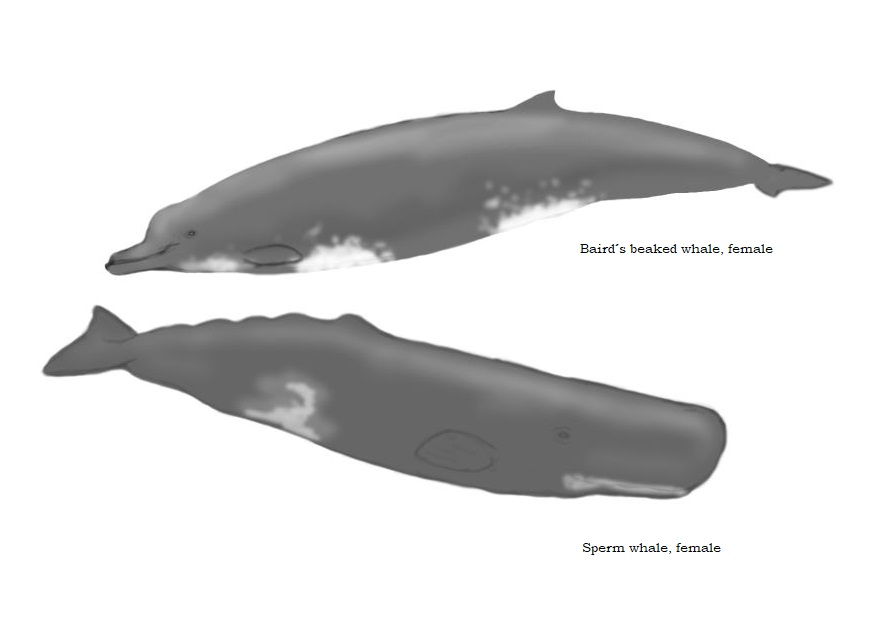

Here is a size comparison of a female B. bairdii with an average female sperm whale which I made during an early version of the illustration.

So far no one has ever seen Berardius hunting but it would be an incredible sight to watch those leviathans patrolling the floor of the north Pacific and sucking in half-meter long grenadiers. That’s why I tried to create an illustration of a hunting Baird’s beaked whale to give you some idea how this could look like. Right now, when you are reading this lines, something like this happens in reality, but in pure darkness. Just think about this, we life in an awesome world.

Berardius bairdii is a comparably opportunistic hunter which feeds on a large number of very different deep sea squid and fish. Grenadier fish or rat-tails make up a big part of their diet. This fish reaches usually lengths of about a 0,5-1 meter and stay usually close to the seafloor. In many areas they are among the most numerous deep sea fishes and make up much of the vertebrate biomass. Some species are even commercially fished. But Berardius also feeds on many other species, from codlings to lancetfish.

From examinations of stomach contents we also know various cephalopod prey species of Berardius bairdii, even small specimens of Architeuthis (the famous giant squid) were already recorded. It seems that hunting occurs mainly close to the seafloor and Berardius can dive at least to depths of 1777 meters.

I looked for various references for the sea floor and the other animals around. The small swarm of fish chased by the whale are Pacific grenadiers (Coryphaenoides acrolepis), the small translucent squid on the right a subadult specimen of Galiteuthis pacifica which is also known from stomach contents of B. bairdii. I also depicted a grey cutthroat (Synaphobranchus affinis), a deep sea eel which is also a known prey species.

Monster carcasses

The giant size, the somewhat unusual anatomy and the unfamiliarity of many people with beaked whales in general and the transformation powers of taphonomy resulted into several cases in which carcasses of Berardius bairdii were mistaken for sea monsters. One of the most famous cases, the Moore beach carcass (featured by Darren Naish at Tetrapod Zoology), is still often claimed as the alleged relics of a modern day plesiosaur. An upside down floating Berardius bairdii was assumed to be a late surviving archaeocete (also covered at Tetrapod Zoology). Another much more recent case from 2015 gained a lot of attention in the international press. The „bird-beaked“ and „hairy“ carcass which washed ashore at Sakhalin Island was assumed to be a giant hairy dolphin, a Ganges freshwater dolphin and even the relics of a mammoth from the permafrost which was somehow washed to the sea. This identifications are all highly absurd and it´s surprising that no real experts were asked for their expertise. The size, the shape of the skull and jaws, the melon and the visible flipper bones all clearly show it was a Berardius carcass, and the „hair“ is just a very common artifact of decomposition when tissue fibres disconects from each othe. Cameron McCormick wrote also about the sometimes bizarre effects of decomposition and scavenging on Berardius carcasses. I included some of those cases also in a talk which I gave in 2018 about „monster“ carcasses, in which I presented various cases of misidentified animals which were claimed to be monsters, „dinosaurs“ or other alleged prehistoric or unidentifiable beings which – according to tabloids and internet news – baffled scientists all the time. I explained how taphonomy can drastically change the appearance of an animal’s body and why cetacean carcasses in particular are so prone to get misidentified as monsters. It was especially important for me to show how you have to systematically examine such cases for the identification from anatomical traits which are usually not affected by mere degradation of soft tissue. But that’s another topic of its own which I want to cover another time.

References:

Leatherwood, S., R.R. Reeves, W.F. Perrin, and W.E. Evans, 1982. Whales, dolphins, and porpoises of the eastern North Pacific and adjacent Arctic waters, A guide to their identification, NOAA Tech. Rept., NMFS Circular 444, 245 pp.

Ohizumi, H., Isoda, T., Kishiro, T., Kato, H., 2003. Feeding habits of Baird’s beaked whale Berardius bairdii, in the western North Pacific and Sea of Okhotsk off Japan. Fisheries Sci 69, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00582.x

Walker, W.A., Mead, J.G., Brownell, R.L., 2002. DIETS OF BAIRD’S BEAKED WHALES, BERARDIUS BAIRDII, IN THE SOUTHERN SEA OF OKHOTSK AND OFF THE PACIFIC COAST OF HONSHU, JAPAN. Marine Mammal Sci 18, 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01081.x

Yamada, T.K., Kitamura, S., Abe, S., Tajima, Y., Matsuda, A., Mead, J.G., Matsuishi, T.F., 2019. Description of a new species of beaked whale (Berardius) found in the North Pacific. Sci Rep 9, 12723. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46703-w